Go  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| Member |

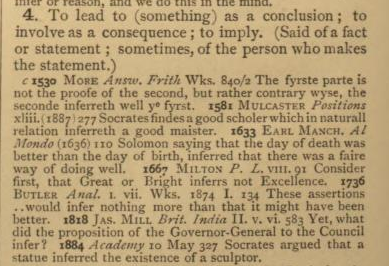

The imply-infer hijacking of the incompatible thread has had me pondering what exactly is the duty of the makers of dictionaries. Whether to describe the language as it is used or to prescribe certain usages while noting them in passing, perhaps labelled as sub-standard or slang or simply just wrong. As the controversy about the hint or suggest meaning of infer did not surface until a hundred or two years after it first developed from the early impersonal use of infer, I thought it would be instructive to see what the Brothers Fowler, fresh from the success of their King's English (1908), had to say in their The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English (1919, link) had to say.  Well, there it is, in plain English, without commentary: one of the meanings of infer is imply. Even seven years later, Fowler, in his Modern English Usage, passes over imply and infer, except to note how their various forms are conjugated. By the time of its second edition, revised by Sir Ernest Gowers in 1965, we have: Sir Ernest, no doubt, could scarcely bring himself to mention that such was the case with the author of the book he was revising, if, in fact, it came to his attention. When a meaning is so common, it is the duty of the lexicographer to record it, for without these recordings, a dictionary's usefulness is diminished. —Ceci n'est pas un seing. | ||

|

| Member |

One of the meanings of infer in the first edition of the dicrionary wrongly called the Oxford English Dictionary, but rightfully called A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles.  Note that this volume was published in 1901 about 16 years before the imply meaning became controversial. [Fixed capitalization problem.]This message has been edited. Last edited by: zmježd, —Ceci n'est pas un seing. | |||

|

| Member |

Damn! It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society. -J. Krishnamurti | |||

|

Copyright © 2002-12